Lycian Legacy – Pinara

Photos by Mike Vickers

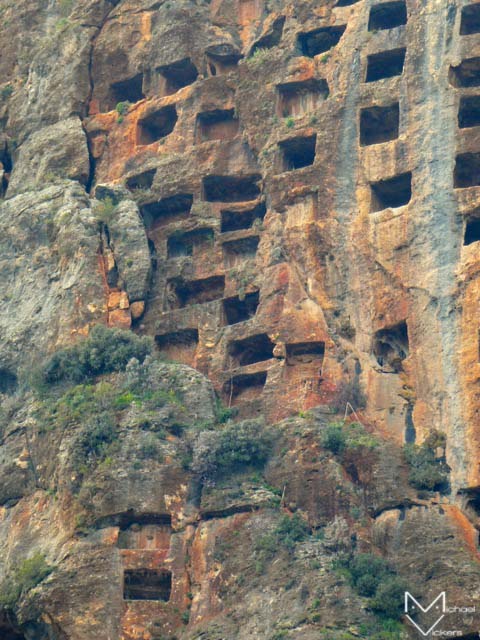

Feature photo above: Like windows in the the side of a skyscraper, dozens of pigeon tombs dot the face of the huge red bluff that dominates the city.

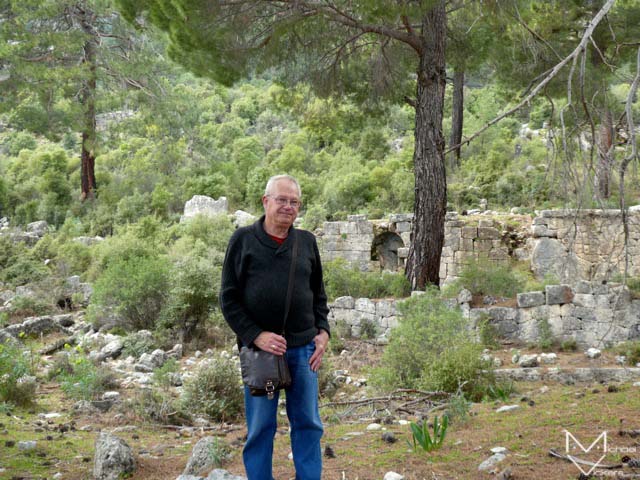

The ruined city of Pinara lies about 50km from Fethiye and is located in a picturesque fold in the mountains above the tiny rural village of Minare, offering spectacular views eastwards across the valley of the Esen river to the high mountains beyond.

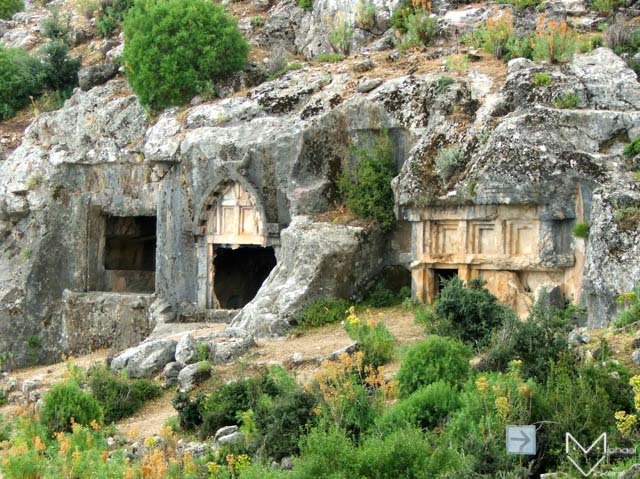

So, where and what was Lycia? Known as the Land of Light, Lycia mainly comprised 23 cities bound together in a loose political league and located throughout the Teke Peninsula, that pregnant bulge of modern Turkey which hangs down into the Mediterranean Sea between Fethiye and Antalya. Later Greek and Roman civilizations were added on top of these original settlements, giving each building unique architectural identifiers. In the very broadest terms, any pillar, pigeon or house rock tomb and any wall with irregular or hexagonal stonework is Lycian, any perfectly proportioned building with squared stone blocks and horizontal lintels is Greek, and anything Greek-looking but also made of brick or with an arch is Roman. That’s the chronological sequence, with Lycian being the oldest, then Greek, and finally Roman. For the sakes of this article, I’m referring to Pinara as a Lycian city as they were the first on the scene.

Like all of the Lycian cities, Pinara has been heavily damaged by earthquakes over the centuries and was abandoned long ago. Very few buildings now remain, but the one main structure still existing is the small and almost perfectly preserved Greek theatre. This lies across a small narrow valley and faces back towards the city, offering a view up to the city itself surmounting a long low terraced ridge located at the foot of the defining feature of the site – a huge vertical tree-topped bluff of rich red rock. This dramatic cliff face is peppered with an astonishing number of shallow rectangular pigeon hole tombs, giving it the appearance of windows in the side of a modern skyscraper.

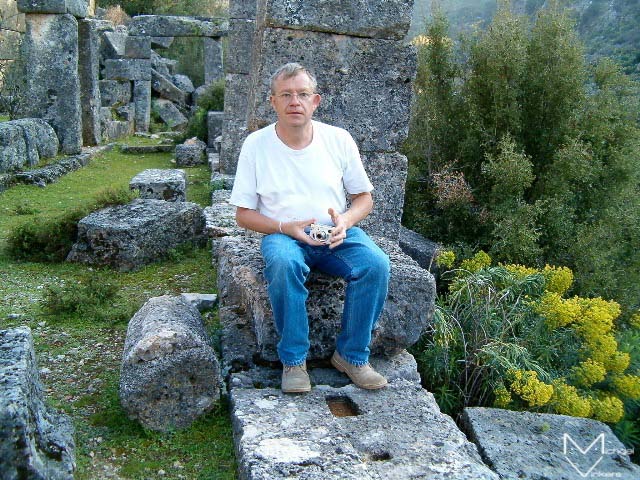

The city below is an extensive shambles of grey stone blocks poking up at every angle. The bases of some temples remain, including one thought to be dedicated to Aphrodite, as identified by its unique heart-shaped columns. Very little else is recognizable but for a few walls here and there and the shattered remains of the agora.

To reach this entails scrambling between piles of fallen masonry covered in bushes. Stones still lie as they fell centuries ago, piled in jumbled disorder everywhere, but there is a narrow path that will take you to the far end of the agora where a well-preserved flagged platform overlooks a deep ravine with more tombs carved into its walls. I once managed to climb up this ravine with my sister during a thorough exploration years ago, but there’s no way I’d attempt that perilous ascent nowadays. My knees just aren’t what they used to be…

As far as I know, there is only one very small area of surviving mosaic in Pinara. I found it 16 years ago covered with a flat stone for protection. Amazingly, considering I normally cannot remember what I had for breakfast, I quickly found the same stone again when I visited a few weeks ago and sure enough, the diminutive mosaic was still preserved beneath.

The road that leads to Pinara actually continues on through the site and climbs up behind the red bluff, where there are further buildings. I’ve never had the chance to explore that part of the city, but don’t let me stop any of you from having a peek.

For me personally, Pinara is a really rather special place. Its mountain location well off the beaten track means there are seldom other people at the site – I think the most I’ve ever encountered is four. I like that. Pinara is the one place where I really want to be alone. One of my great memories of Turkey, among many, is sitting in solitary isolation amongst the pines surrounded by the ghostly ruins and looking out over the theatre and away across the broad Esen valley to the soaring snow-capped Akdağ mountains behind. The only sound I can hear is the soft moaning whisper of wind in the pines above my head, like ghostly whisperings of the past. In those wonderfully ethereal moments, I always find myself wrapped a warm and deep inner peace and, for just a few minutes, a sense of complete, total and utter contentment.

Dreamy Pinara is a place like no other!

Directions: Leave Fethiye on the D400 and keep following the signs to Kaş. After 40km or so, once you’ve passed through the village of Çaykenarı, look out for a right turn onto a minor road signed to Minare. A brown sign indicates this is also the turning for Pinara. A few kilometres up this road, just as you enter Minare itself, another brown sign to Pinara points off to the left. Follow this newly-paved road for several kilometres up into the hills via several impressively sharp hairpin bends until you reach the city. The appearance of a car park and guardian’s hut with toilets indicates you’ve arrived at your destination. If the hut is occupied, you’ll have to pay a modest entrance fee, if not, you don’t. This fee is also waived if you posses a Muze card, which, luckily, I do.